Lynnfield Meeting House

Built in 1714, the Lynnfield Meeting House at 617 Main Street is one of the oldest surviving Puritan meetinghouses in Massachusetts, anchoring the town’s original civic core. Its timber-frame construction, clapboard siding, multi-pane sash windows, and prominent steeple offer a textbook example of early New England ecclesiastical architecture. Restoration and preservation work here often focuses on structural stabilization, exterior envelope repairs, and sympathetic upgrades that maintain its National Register–listed character.

Phone: (781) 334-3555

Meetinghouse Common Historic District

The Meetinghouse Common District surrounds the town green and includes a collection of colonial, Greek Revival, and later-period residences and civic buildings. Listed on the National Register of Historic Places, the district showcases original wood framing, traditional clapboards, stone foundations, and mature landscape features that define Lynnfield’s historic village character. Any exterior envelope work or infill development here must respect historic massing, materials, and sightlines.

Phone: (781) 334-9400 (Town of Lynnfield)

Lynnfield Town Common

The Lynnfield Town Common is the central green fronting the Meeting House, framed by historic homes, churches, and civic buildings. The open lawn, mature trees, monuments, and surrounding streetscape form a key visual corridor for any municipal infrastructure or streetscape improvements. Projects around the common often require sensitivity to pedestrian circulation, lighting, drainage, and masonry work that preserve its historic ambiance.

Phone: (781) 334-9488 (Recreation & facility inquiries)

Lynnfield Town Hall & Municipal Offices

Lynnfield’s municipal government is headquartered at 55 Summer Street, providing administrative offices, meeting space, and permitting functions for the town. The building’s civic scale, parking layout, and accessibility features make it a focal point for public-facing improvements such as envelope upgrades, energy retrofits, and stormwater management. Any renovation or expansion work must balance modern performance standards with an exterior compatible with the historic center.

Phone: (781) 334-9400

Lynnfield Public Library

Located at 18 Summer Street, the Lynnfield Public Library is a key civic structure that blends traditional New England styling with contemporary interior upgrades. Large window openings, brick and masonry detailing, and planned improvements to meet modern library standards make it a frequent site for envelope restoration and accessibility projects. Designers and contractors working here must coordinate building systems upgrades with community expectations for a welcoming public space.

Phone: (781) 334-5411

MarketStreet Lynnfield

MarketStreet Lynnfield at 600 Market Street is a large open-air mixed-use center with more than 80 shops, restaurants, and civic event spaces. The property showcases modern retail facades, brick and stone storefronts, structured parking, pedestrian plazas, and seasonal programming that draw regional visitors. For commercial contractors and envelope specialists, the site offers examples of façade modernization, tenant fit-outs, and coordinated site drainage in a dense suburban environment.

Phone: (781) 484-5400

Our Lady of the Assumption Church

Our Lady of the Assumption Church at 758 Salem Street serves as a major Catholic parish for Lynnfield and neighboring communities. The church’s traditional sanctuary, stained glass, masonry walls, and attached parish facilities present ongoing needs for roof work, masonry repointing, and envelope waterproofing. Contractors working on religious structures can reference this site for best practices in maintaining liturgical spaces while integrating modern life-safety and HVAC systems.

Phone: (781) 598-4313

Saint Maria Goretti Church

Saint Maria Goretti Church at 112 Chestnut Street is a mid-20th-century parish with a simpler modernist profile than many older New England churches. Its broad roof planes, brick walls, and parish hall spaces create opportunities for energy retrofits, accessibility upgrades, and site improvements that must respect residential abutters. The property is a useful reference for phasing exterior repairs and parking lot work around ongoing congregational use.

Phone: (781) 598-4313

Hart House (172 Chestnut Street)

The Hart House at 172 Chestnut Street is a First Period saltbox dwelling dating to the late 17th century, listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Its central chimney, asymmetrical roofline, and exposed timber framing illustrate early construction techniques and later-period additions. Preservation work here focuses on foundation and sill stabilization, historic window and clapboard repair, and careful moisture management in an aging wood-frame envelope.

Phone: (781) 334-9400 (Lynnfield Historical Commission via Town Hall)

Henfield House (300 Main Street)

The Henfield House at 300 Main Street is another First Period saltbox home, with portions dating to around 1700 and subsequent early-18th-century expansions. Its steeply pitched roof, central chimney, and later dormer additions tell a layered story of domestic architecture over three centuries. For historic restoration specialists, the property exemplifies challenges in integrating modern utilities and insulation into an early frame while preserving original fabric.

Phone: (781) 334-9400 (Lynnfield Historical Commission via Town Hall)

Lynnfield High School

Lynnfield High School at 275 Essex Street is a modern educational campus serving the town’s secondary students. The building complex includes classroom wings, athletic facilities, parking areas, and service courts that require coordinated site drainage, pavement maintenance, and exterior envelope upkeep. Capital projects here often involve roofing systems, masonry control joints, and additions that must tie in structurally and architecturally to the existing facility.

Phone: (781) 334-5820

Lynnfield Middle School

Lynnfield Middle School at 505 Main Street is a sizable institutional structure situated near the historic center. Its classroom blocks, gymnasium volumes, and service areas highlight typical details for late-20th-century school construction, including brick veneer, flat roofs, and large mechanical loads. Renovation and expansion work here must address thermal performance, façade longevity, and circulation patterns for buses and pedestrians.

Phone: (781) 334-5810

Summer Street Elementary School

Summer Street Elementary School at 262 Summer Street serves younger students in a neighborhood setting. The low-rise classroom wings, playgrounds, and driveways present typical K–5 design concerns such as secure entries, drop-off circulation, and child-friendly outdoor spaces. Future improvements often include façade upgrades, window replacements, and roof work that enhance energy efficiency while maintaining a welcoming scale.

Phone: (781) 334-5830

Huckleberry Hill Elementary School

Huckleberry Hill Elementary at 5 Knoll Road is another key neighborhood school with a compact site and surrounding residential streets. The building’s brick and concrete envelope, window patterns, and roof assemblies provide reference conditions for typical mid-century school rehabilitation. Site improvements often address drainage, retaining walls, and playground surfacing in coordination with building envelope repairs.

Phone: (781) 334-5835

Our Lady of the Assumption School

Our Lady of the Assumption School at 40 Grove Street is a parochial K–8 facility adjacent to the church campus. Its classroom building, gym and play areas sit within a tight parcel, making circulation, parking layout, and stormwater control especially important for any site work. Envelope maintenance, masonry repairs, and mechanical upgrades must be planned around the school calendar and coordinated with parish operations.

Phone: (781) 599-4422

Reedy Meadow Golf Course

Reedy Meadow Golf Course at 195 Summer Street is a 9-hole facility woven into wetlands and open space near the town center. The clubhouse, cart paths, and associated site structures must coexist with sensitive marshland, demanding careful grading, drainage, and erosion control. For civil engineers and site contractors, the course demonstrates how recreational infrastructure can be integrated into conservation land.

Phone: (781) 334-9877

King Rail Reserve Golf Course

King Rail Reserve Golf Course on King Rail Drive is a walking-friendly course located near Reedy Meadow’s wetlands. Its low-impact design, boardwalk-style crossings, and proximity to conservation areas require careful attention to stormwater, habitat protection, and resilient landscaping. The clubhouse and maintenance buildings provide case studies in siting small structures within a constrained environmental footprint.

Phone: (781) 334-9877

Reedy Meadow & Partridge Island Boardwalk

Reedy Meadow, accessed via the Partridge Island boardwalk near Main Street, is one of Massachusetts’ largest freshwater marshes. The floating boardwalk, viewing platforms, and trail structures illustrate how lightweight construction can traverse sensitive wetlands. Designers and municipal planners can look to this site for examples of low-impact foundations, treated wood detailing, and public access that aligns with conservation goals.

Phone: (781) 334-9400 (Town Conservation & Open Space)

Lynnfield Center Water District

The Lynnfield Center Water District facility at 83 Phillips Road houses wells, pumps, and control systems that serve much of the town. Its small campus blends industrial components with a residential-scale exterior, requiring secure yet unobtrusive fencing, paving, and access drives. Infrastructure projects here focus on tank rehabilitation, equipment buildings, SCADA system upgrades, and resilient utility design.

Phone: (781) 334-3901

Lynnfield Water District (South Lynnfield)

The Lynnfield Water District at 842 Salem Street provides water service to South Lynnfield and neighboring areas from its district office and associated infrastructure. The site combines administrative space with operational facilities, including underground utilities, paved yards, and storage. For contractors, the district illustrates the needs of aging utility campuses—septic replacement, paving reconstruction, and small building renovations coordinated with continuous operations.

Phone: (781) 598-4223

Camp Curtis Guild (Lynnfield Portion)

Camp Curtis Guild is a Massachusetts Army National Guard training camp spanning Reading, Wakefield, and Lynnfield, with access from River Road in Reading. The Lynnfield portion includes training ranges, wooded buffers, and utility corridors that intersect town boundaries, requiring coordination on telecommunications and infrastructure projects. Any work near the reservation must account for security protocols, environmental constraints, and regional emergency communications needs.

Phone: (781) 944-0500 (Camp Curtis Guild)

Also Read:

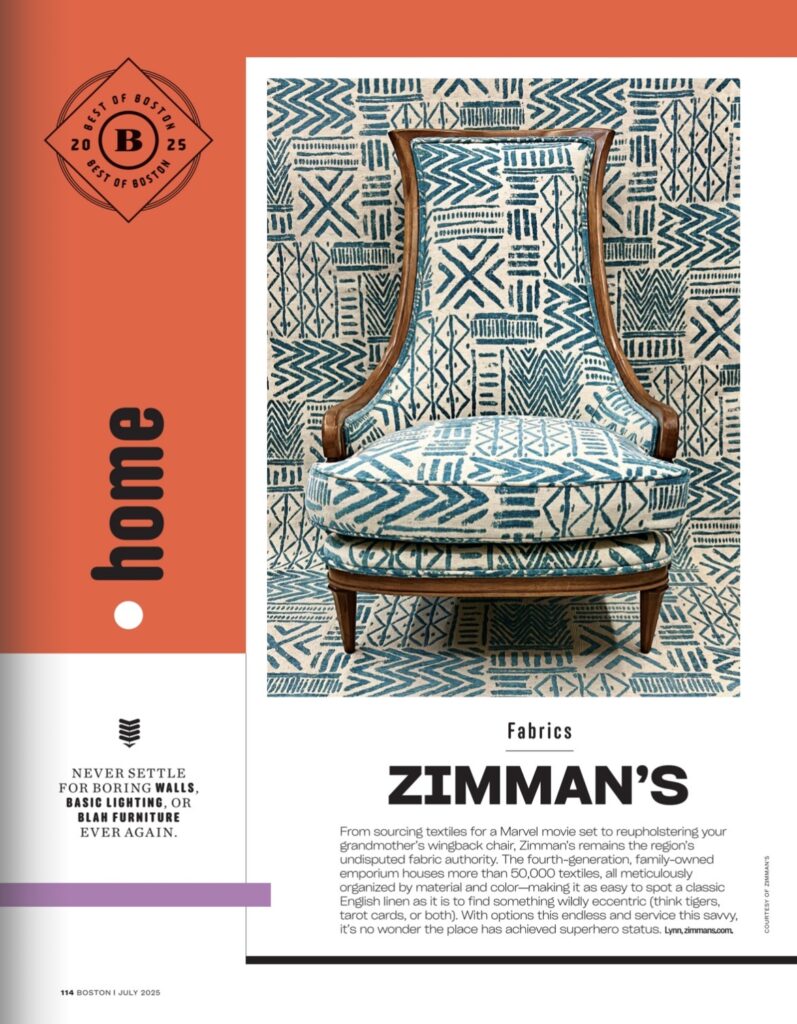

How Custom Slip Covers Can Instantly Transform Your Furniture

Why Choose Reupholstering Furniture Services Over Buying New

How Custom Window Treatments Create the Ultimate Living Space

Best Fabric Store Near Me: Where to Find Unique Textiles and Great Deals

Reupholstering Services Near Me: Transforming Furniture with Style & Durability